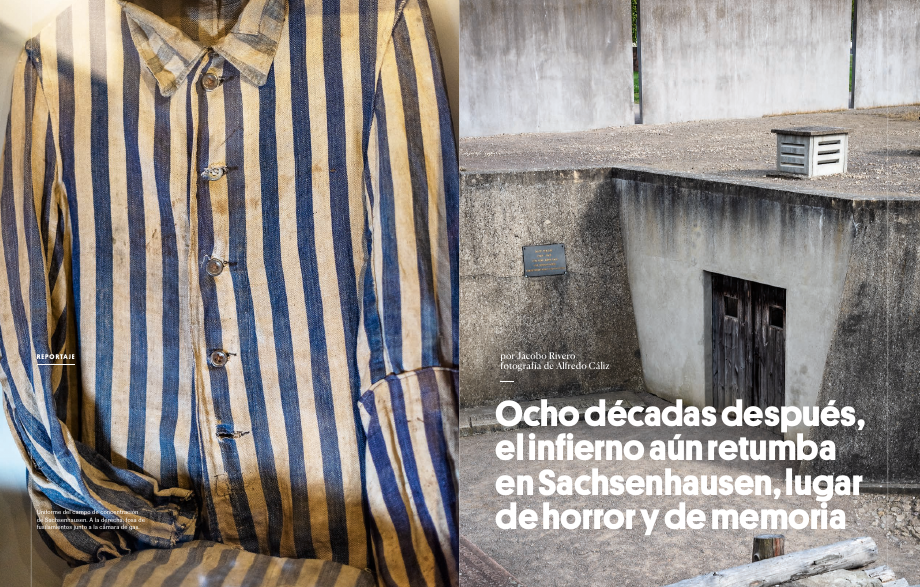

Report by Jacobo Rivero for El Pais Semanal

More than 200,000 people were imprisoned in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp between 1936 and 1945. Tens of thousands died from disease, starvation, forced labor, medical experiments, torture, gas chambers or were victims of SS executions. It was a center conceived by its leader Heinrich Himmler as a “model” camp for his extermination policy. Descendants of the survivors now collect the legacy of the memory of their families to not forget what happened in the past, to denounce the horrors of the present and to project a future in which something similar will not happen again.

Jacobo Rivero

To get to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp you have to take a bus line H from the center of the city of Oranienburg, 35 kilometers from Berlin, in the state of Brandenburg. The town of just over 45,000 inhabitants is a quiet, cobblestone streets with an abundance of single-family homes. The directly elected mayor, Alexander Lasesicke, is an independent politician who formerly belonged to the Greens and the SPD. The corporation has six councillors from the social democratic SPD, six from the conservative CDU and four from the far-right Alternative for Germany party. The bus heads down the Street of Nations to make a stop in front of the entrance to the memorial of the former concentration camp, where groups of tourists get off every day and where residents continue their journey accustomed to the bustle of visitors. Both sides of the street are lined with manicured gardens and sturdy houses with gabled roofs to prevent snow accumulation in winter. These homes once belonged to Nazi officers assigned to the concentration camp. Next to the houses are two large buildings with an athletics track. There was an SS training school there; today it is a German police academy. A sign inside the premises warns the curious who walk between the outer wall of the concentration camp on one side and the fence of the school for agents on the other: “As part of their studies, the students learn about the history of what happened here and the crimes committed by the police under the Nazi regime”.

Thousands of prisoners imprisoned at Sachsenhausen walked the same path and others nearby. They did it every day to reach the work centers assigned to them in conditions of constant slavery and mistreatment. Life there was worthless, death could come at any moment. George Saxon is the son of Tadeusz Witkowski, a Polish inmate who survived the concentration camp and had to make that journey many times. Saxon sports reddish hair and style in spades. He grew up in a “tough, poor neighborhood” in London and identifies with Joe Strummer, the lead singer of the punk band The Clash, whom he was lucky enough to see live as a young man. With an affability that grabs you from the first moment, Saxon remarks that his favorite phrase in Spanish is “No pasarán!”. Since 1974 he has been doing performance and art pieces for video and audio, but in 2021 he retired as an art teacher. He belongs to the second generation of descendants of concentration and extermination camp survivors: “Memory must never be forgotten. Places like this are very important, the legacy of our families must remain alive,” he says from the Sachsenhausen center. In 2003, during a renovation inside the camp, a worker found a bottle hidden in a wall. Inside was a piece of paper written by George’s father and communist prisoner Anton Engermann, both indicating their prisoner numbers, date of birth, day of entry into the camp and when the note was written. Engermann further wrote: “I want to go home again, when will I see my love in Frechen, Cologne? My spirit is intact, things will get better soon.” It was April 19, 1944, still a year before the liberation of the camp. Both survived.

George Saxon is in Sachsenhausen as part of an international gathering of descendants of survivors under the title Voices of the Next Generations. The meeting, held between September 15 and 18, aims to bring together the diversity of the group’s origins as a driving force to intervene in the present. The meeting is behind closed doors and from the first moment they have connected despite the diversity. The meeting brought together some thirty people from very different backgrounds. In the conversations they talk about the war in Ukraine, the situation of refugees or the rise of extreme right-wing parties in many countries. There is a common idea among many of them: banish the concept of heroes when talking about their relatives. “I don’t like that word,” says Saxon categorically, “what does that mean, is a hero someone who shoots to achieve a victory, someone for dying in a war? It seems to me that that often takes us away from the issue, and it happens sometimes with how the media treats the issue.” He says this with a good tone, laughter and a strong London accent. “Our families were survivors, we are children and grandchildren of survivors. We have to make it understood that as societies what happened to my father and many others is not just my problem, but everyone’s problem,” she adds.

Amelie Reichmuth shares the same opinion. She works in Stockholm as an economic journalist for a start-up. “The story of our families is like an open door. They were ordinary people who got caught in a spiral of hatred. The big learning is that we have to get involved every day in respecting the human rights of all people, whatever their background and beliefs. We have to listen to the stories of people who are suffering and tell them: ‘I am here to help you’. And so create a movement that brings us back to the category of citizens and not just consumers, where everything seems to be solved through social networks and individualism.” Reichmuth declares herself a militant optimist, although she knows that the world is not exactly moving in that direction. Her tone is slow and deep, her speech projects a human warmth with which she feels committed: “We have not chosen this path, it has come through our families and we cannot separate our private life from the political. In this meeting I say that we are messengers. If we make our experience known, perhaps in this way we can build a better world, and I must apply this reflection to the way of life I lead because it also has to do with climate change, social justice, racism, wars or the sustainability of the planet”. Reichmuth’s gaze has light and transmits emotion when she speaks, her sighs are also full of feelings.

In Sachsenhausen the sound of the leaves of the trees that surrounds a large part of the enclosure generates a situation of strange harmony. The winds of the past and the present mingle. Elias Mendel doubts whether some of these trees shared a life time with his relatives. Mendel is clear that he conveys his commitment through his illustrations, there he finds a connection with what happened to his grandfather, a Berliner who was locked up in Sachsensahusen in the part reserved for Jewish barracks. His notebook is full of black and white drawings that transmit a force that comes from the gut. Sometimes he projects them on significant Nazi buildings. He does not rule out doing so on one of those surrounding the concentration camp, where the SS members used to live.

Elias Mendel is critical of how memory is often managed by institutions: “We must understand what happened and also learn from our mistakes. Because we have to break the idea that this cannot happen again, because this is already happening in many countries”. And he adds in relation to the current context: “The generation that lived through this is dying and the extreme right is taking advantage of this vacuum, it is very important to continue remembering history and denouncing fascism”. Mendel also strongly reproaches the lack of justice after World War II. Of the more than

3,500 SS members who operated at Sachsenhausen, less than six percent were tried. Liberated by the Soviet army in its advance towards Berlin, the Nazis left about 3,000 people in the camp, most of them very sick. The SS evacuated the camp in an escape that dragged with them most of the inmates in the so-called Death Marches, in which thousands of prisoners perished. On that infernal journey was the former president of the Spanish Republic between 1936 and 1937, Francisco Largo Caballero. The socialist politician was one of the more than 200 registered Spaniards who suffered the atrocities of the concentration camp. Sachsenhausen is the most requested visit by Spanish tourists visiting Berlin, according to several guides. Hugo J. Sánchez Rey from Seville is one of them. He translated into Spanish the book Era la noche, a long interview of two French history professors to the last Spanish survivor who left the concentration camp: Pedro Martin. The son of Spanish emigrants in France and a member of the Resistance, he was one of the seriously ill left behind by the Nazis in their escape. He lived to the age of 95 and died in April 2020. His testimony also speaks of solidarity among prisoners, of sabotage in factories and daily struggles for life. Obviously also of terror and death. Many tourists do not know that there were also Spaniards in the concentration camps. Rayco and Lucas come from the Canary Islands and are in their thirties. Before taking the H-bus back to the center of Oranienburg, the former confesses his feelings after the visit to the concentration camp: “It is moving, overwhelming and anxious. His friend adds: “One thing that is striking is that despite the traumatic, there is a need to know the history of Europe to look to the future. Here come the schools and in Spain there are still obstacles to take that step”.

Hirsh Litmanowicz, born in 1931, speaks precisely about looking to the future. Locked up in the Warsaw ghetto in 1942, he was separated from his entire family a year later when he was deported to Auschwitz at the age of eleven. From there he was sent to Sachsenhausen with eleven other Jewish children so that Nazi doctors could experiment with the effects of hepatitis B on them. His granddaughter Danielle Chaimovitz is present at the meeting of the new generations. Before attending, her grandfather said to her over the phone, “Why do you want to go to hell?” Hirsh answers by phone call with his granddaughter present in the room, the call is hands-free and there is a special atmosphere in the room where we make it. She has never talked much to her grandfather about what really happened, it is a subject that still causes a lot of pain in a family where her grandfather and grandmother lost all their relatives. “I was a child, I didn’t understand the reason why the Germans did that to us. Those eleven children we were a family, we cried in pain because of what they did to us and also because we knew what had happened to our families. I know how they killed my uncles, my sisters, my parents.” He says this in a strong and determined voice. When the liberation came he was 14 years old. “I was alone in the world, I didn’t have any relatives. I depended on someone to do me a favor. At 18 I was able to travel to Peru, where I live, and start from scratch with my wife and have a happy family.” For him, memory is fundamental in these times: “The past cannot be erased, the past exists. I remember everything. I see what is happening in the world and I think that Putin is another Hitler. Those of us who suffered will take it to our graves, but I do want our families to remember our legacy, to never forget it, to let people know what happened. Hirst Litmanowicz is 91 and the youngest of the Sachsenhausen survivors. Around 45,000 people died in the concentration camp.

Her granddaughter Danielle attends the conversation with restrained emotion. She is 36 years old and has three children, currently living in Estonia; her husband is the grandson of a partisan. She says that the Holocaust has been present in her life since she was a child. For her, who defines herself as a “religious Jew” and observes the ritual of the Sabbath, meeting other descendants of survivors has been very useful: “There are people who have come here and tell how their relatives actively fought against the Nazis and that is why they brought them here. My grandfather all he did was be a Jewish boy. Listening to those other voices I realize that not everyone was bad at that time. That gives me a lot of hope, it means that if I passed by them on the street without knowing us I wouldn’t notice. And now I feel something important, I feel that I can understand other people, with other origins. In Sachsenhausen the first inmates were political opponents of the National Socialist regime, then those who were considered racially or biologically inferior, and from 1939 onwards, citizens of the countries occupied by Germany. There were communists, socialists, anarchists, gypsies, homosexuals, Jews, Catholics, evangelicals or soldiers from different armies. For Danielle, meeting other descendants gives her a new reason to get involved with her family’s past: “We have to do more for Sachsenhausen, for the place that gave us the opportunity to know each other. I think for example of Ukraine, of the people who are suffering and fleeing the war. I want my children to know that we did everything we could to help. Because this time will one day also be history.”